Heritage in our foundations

What lies beneath Brougham St? A team of archaeologists helped us find out.

Underground Overground Archaeology monitored cutting and digging, including this trench running beside what will become Hoiho Lane. PHOTO: Underground Overground Archaeology

The Dunhams didn’t go far to dump their rubbish. They buried their food scraps, broken crockery and empty bottles on their section, just as many of the people who lived along their street did.

They and their neighbours threw out plates and cups, Worchester sauce bottles and chamber pots. Eventually, even with boot makers on the street, they buried their tired leather shoes.

Sometimes they even didn’t bother to excavate a pit, leaving their rubbish exposed and stinking on hot days. It sounds terrible now, but it was common practice in the 19th century.

We know about their tipping habits because their rubbish stayed buried until 2020, when the pits and the detritus they left were carefully uncovered during one of Christchurch’s biggest community housing builds.

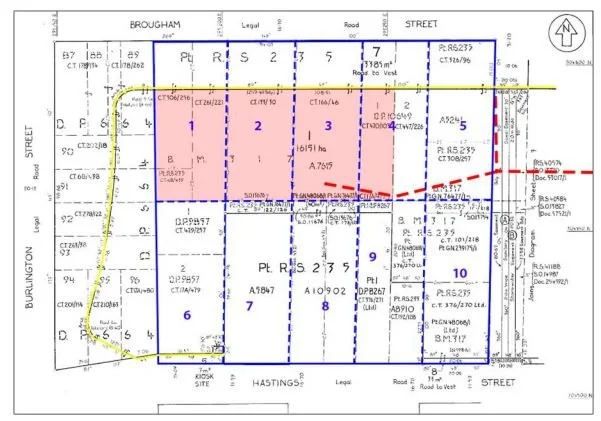

Archaeologists from Underground Overground Archaeology were there as the foundations for dug and the service trenches were cut on the site of Ōtautahi Community Housing Trust’s 90-home Brougham St development.

They had to be: they knew the site was occupied as the fledgling city grew in the 1800s, and they knew three recorded archaeological sites may be disturbed during earthworks.

It soon became clear there was more to see than the remnants of Brougham Village, the 1970s-built community housing complex the new development would replace.

About half the area of 356-402 Brougham St was excavated to a depth of 1m, exposing 21 archaeological features and four archaeological sites to be added to the official list.

The Dunhams

Among them was land once owned by Samuel and Elizabeth Dunham – land that will be home to a dozen new housing units facing the soon-to-be-formed Hoiho Lane.

The land was not far from what is now the corner of Brougham and Burlington Sts when Elizabeth bought the first of two lots in 1878. Then, the address was on Lord Brougham St.

The British migrants moved there from Heathcote Valley, where at least one of their children – John – was born years earlier. He’d marry Margaret Wilson, a dressmaker, there in March 1888.

The 21-year-olds tied the knot before their parents and John’s brother Charles, and sister Emily. John’s other brother, George, was not named as a witness; he’d have been 24 years old.

The Dunhams were workers. Samuel was a labourer, John was a clicker (a job in either the shoe or printing trades), Charles was a compositor, and Emily was a boot maker.

Five years later, Emily would be one of the first women to sign the Christchurch pages of the Women’s Suffrage Petition. She’d also own at least one rental property in Sydenham – a property that, in 1918, would feature in a divorce case featuring a tenant who shacked up with another man while her husband was fighting overseas.

Emily had a role model in Elizabeth, who was likely in charge of the family finances. Elizabeth raised the mortgage to buy the property on which they lived, as well-as the land next door.

Alfred Green was there before the Dunhams arrived. The shoemaker arrived from England with his wife and three daughters in 1865, the same year as another new owner.

Elizabeth sold the second of the two lots she owned to Benjamin Hale in 1887. He’d been in Christchurch with wife Eliza since emigrating from England in 1865.

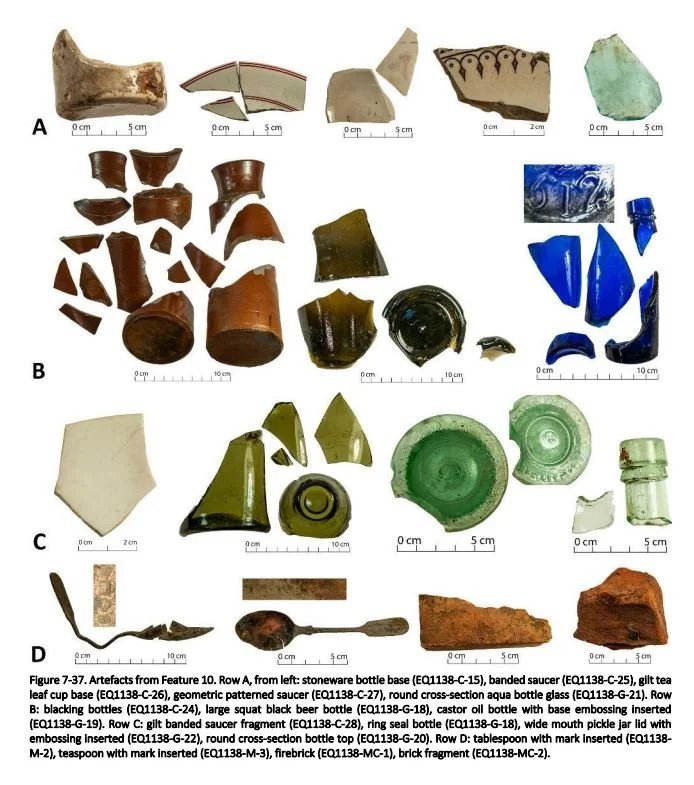

An example of the material Underground Overground Archaeology recorded from sites beside Hoiho Lane. PHOTO: Underground Overground Archaeology

The Hales

Benjamin was a tent, rope, sail and tarpaulin importer and maker who had a shop on Cashel St. In 1872, a newspaper advert declared it had “a variety of goods too numerous to particularise in an advertisement”.

It was a business of its time: tents and tarps provide the first shelter for countless migrants flooding into the new town.

His wares would have been in hot demand. Evidently, Benjamin had the means to buy an investment. The Hales didn’t move to Brougham St and the property was sold to Patrick O’Hara in 1894.

All the while, the people who lived there left remnants of their lives buried on their properties.

The archaeologists found 224 artefacts, made up of hundreds of pieces, beneath what would later become 7-29 Hoiho Lane.

The 19th century pits were described as typical of the time, filled with domestic objects connected with the preparation, storage or serving of food and drink.

An “Asiatic pheasants” design found on some of the broken crockery was common of other sites, and Worcester sauce bottles were as likely found there as anywhere else.

Cockle shells were also found; they were a common food waste found all over the city.

There were more rubbish pits further east, under what would become 31-41 Hoiho Lane. Here, people had lived in a four-room brick house from at least 1879.

A brick-lined well, found near where Frederick Hall used to live. PHOTO: Underground Overground Archaeology

The Halls

Benjamin was a tent, rope, sail and tarpaulin importer and maker who had a shop on Cashel St. In 1872, a newspaper advert declared it had “a variety of goods too numerous to particularise in an advertisement”.

Frederick Charles Hall bought the property in 1867, soon after he, wife Sarah and their four eldest children arrived in Christchurch from England.

He had already racked-up the sailing miles: he was born in Sydney in 1834, the son of a tailor, before his family returned to Stepney, London, before 1841.

He married Sarah when he was 22 and was working as a solicitor’s clerk in London when the first four of his 10 children – five boys, five girls – were born.

In New Zealand, Frederick continued to work as a solicitor’s clerk for Wynn-Williams, then Hanmer and Harper, before becoming the “confidential book-keeper” for Ackland and Campbell.

He worked for some big names, but he soon became a big name locally.

He was the first chairman of the Waltham School Committee and then the combined Colombo Rd School District. Frederick gave free French tuition to Sydenham school pupils at night school, once a week. He also helped establish the Societe Francaise.

His was one of the first homes built of permanent materials on that block of Brougham St and, naturally, he was one of the earliest promoters of the formation of the Borough of Sydenham.

Frederick served on the new council from 1879, at a time bearded local representatives were grappling with ways to improve the health of the increasingly polluted settlement.

The city’s waste ran into the Avon and Heathcote rivers, and kitchen waste and chamber pots were emptied into channels that lined the streets or were tipped into garden pits.

The fetid city reeked to high heaven.

It had plenty of good, fresh water from artesian wells, but not everyone had easy access to public water supplies or private wells.

The Halls likely drew their water from a small, brick-lined well that excavators would find when they cut the foundations for where 33 Hoiho Lane would be built.

The well was made with bricks made locally sometime in the 1860-70s. There’s a maker’s mark on the bricks – DBL or DHL – but which company made them is still a mystery.

The well was filled with rubbish sometime in the 20th century, when the water table dropped below the well’s bottom. It became the ideal spot for another rubbish pit.

A waiting room sign was found near where Frederick Hall used to live. PHOTO: Underground Overground Archaeology

The archaeologists also found a blue and white enamelled “Waiting Room” sign. This was a surprise, as there was no record of a business being run on-site.

It’s possible Frederick was conducing official business at home, though: he was French consul, and acting French consul, for many years before the family left the property in 1895.

Also in the excavated area was a glass bottle dump, made up mostly of alcohol bottles, condiment containers and pharmaceutical bottles. It was typical of material from the 1860s-70s, and typical of finds at other sites across the city.

What now?

The archaeological sites were marked and the contents that was removed was cleaned and examined. Then, the material was carefully reburied where it was found. The archaeological features, including Frederick’s well, the Dunham’s pits and some fence post holes, stay where they are.

Future earthworks that might affect those features, or features that might be in areas that have yet to be excavated, will need an authority from Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Tonga.

None of what was found was assessed as being historically significant, but archaeologist Angel Trendafilov said what was found was “like an open window to the past”.

The “chance to look through that window during the course of this project was pretty special”, she said.

What’s now reburied remains in place as a special kind of repository for recently unearthed social history. It’ll stay there for a while – the new Brougham St homes are designed to last for decades – as an echo of old Christchurch, carefully covered and supporting the foundations of a modern community housing development.

* All archaeological material in this article is from Underground Overground Archaeology’s report: 356-402 Brougham St and 95-97 Hastings St West, Christchurch; Report on archaeological monitoring under HNZPT authority 202/682 eq. Angel Trendafilov, Annthalina Gibson, Clara Watson. You can read the full report here.

* The biographical information is from newspaper and family research sources.

ŌCHT’s Brougham St development, from Brougham St.